Contents

- 1 Something writhes in video game horror’s dark underbelly; it has been doing so for years.

- 2 Have you seen how the sun’s rays reflect on Castle Dimitrescu’s marble floors?

- 3 Dread Delusion.

- 4 There’s also something about the tactility of physical media which is gratifying.

- 5 They can prime the player’s mind to be surprised and creeped out.

Something writhes in video game horror’s dark underbelly; it has been doing so for years.

But lately, convulsions have grown violent and the hideous mass threatens to spill over into the mainstream where more respectable nightmares reign. The likes of Resident Evil and Alan Wake are now adhering to the same rules governing spectacle as the latest FIFA or Call of Duty installment, terrifying you at pristine 4K resolutions. This is the ninth console generation currently shaping our entertainment landscape, after all, and there are certain expectations as regards visual fidelity.

Have you seen how the sun’s rays reflect on Castle Dimitrescu’s marble floors?

New retro horror scoffs at such notions of verisimilitude. It will draw the curtains to keep volumetric lighting out and puke all over the exquisite tiling so you’re not distracted by its intricate patterns. A steady procession of brash alternatives to the handful of dominating franchises (as well as the mid-budget imitations) has been making its presence felt recently.

These games are inspired by long-obsolete genres implementing unconventional mechanics and evoking memories from the medium’s rich past. Wildly divergent, this new generation of lo-fi horror games is united by a shared philosophy: treating earlier, era-specific styles from the crude polygons of the original PlayStation to 1-bit monochrome palettes not as intermediary failures on the path to some dubious ideal of “realism,” but embracing them as valid aesthetic springboards in their own right.

And people have been paying attention. In the last couple of years, the scene has exploded. Puppet Combo — who has been turning his favorite childhood VHS slashers into low-poly gore-fests for about a decade — has just started his own production company, Torture Star Video, mobilizing his popularity to highlight the talents of other creators in the niche. Two ongoing anthology series, The Haunted PS1 Demo Disc and Dread X Collection, have revitalized a format oddly neglected in the medium.

And themed game jams have imposed time and theme constraints on developers consistently producing some of the most imaginative work in the field, exemplified by Teebowah’s Game Boy-inspired creepy excursion in Fishing Vacation and Ben Jelter’s trailer-park enigma of Opossum Country. But what has prompted the sudden surge of popularity for such archaic iconography? And why the disproportionate focus of such efforts on horror?

Dread Delusion.

A partial answer to the first question is glaringly obvious. Nostalgia has emerged as a pervasive cultural force in the last decade, from synthwave YouTube playlists to Stranger Things. Why should gaming be exempt from its influence? Under the alias -IZMA-, Adam Birch released Deadeus for the Game Boy in 2019, a Lovecraftian small-town mystery in the vein of classic JRPGs. He admits nostalgia is part of what motivates him.

When I was a kid growing up, I had a Game Boy and had friends with Mega Drives and SNES. That era is seared into my brain because of [these consoles]. It stands to reason that, when people finally achieve the ability, they’d attempt to make games similar to those that made them fall in love with it all in the first place.

The generational angle is certainly consistent with the timeline of the phenomenon. Roughly a decade separates the establishment of pixel art as a viable aesthetic even for mainstream games (such as the 2011 iOS hit Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP which sold more than a million copies) from the crude polygons and grainy video currently in the ascendant. The time span neatly corresponds to the gap between the heyday of the 8-bit platforms referenced by the former and the release of Sony’s groundbreaking PS1 console that inspires the latter — or the period during which a new crop of indie developers could have come of age.

There’s also something about the tactility of physical media which is gratifying.

James Wragg, creator of standout Haunted PS1 Demo Disc entry Dread Delusion, corroborates, albeit with an important caveat. “A lot of it is nostalgia, sure — the PlayStation start-up music will forever stimulate a cluster of neurons in my head. [But] there’s also something about the tactility of physical media which is gratifying; just as book lovers will relish the smell of a new book, flipping through a manual before you pop a disc in a PS1 drive is a more enticing ritual than clicking a ‘download’ button.” Nostalgia may be a universal impulse, but its siren call is most effective when it responds to a certain lack.

Birch believes the lack is not so much about the paraphernalia that used to accompany a game’s packaging (even as he catered to that need by also releasing Deadeus as a physical cartridge) but of a sufficiently diverse range of stories and experiences within the blockbuster sphere. “It has almost become a cliche that there will be a bloated overworld map with 1,000 similar tasks and some watchtower to climb. This on top of a climbing price tag and an almost ‘safe’ approach to subject matter all paves the way for completely off-the-wall, cheaper indie games to go down some dark story paths and fill the void.

As for developers, a different sort of lack may account for new retro horror’s appeal: the ability to compete with big-budget spectacle. “Using low-poly models or creating 1-bit visuals is a much more sensible option for most indie devs who might be more interested in telling a story or inducing specific feelings than in movie-realistic graphics,” says Laura Hunt, co-creator of the decidedly unrealistic but visually stunning cosmic-horror adventure If On A Winter’s Night, Four Travelers. While she has worked on perennial favorite Adventure Game Studio, a wider range of accessible specialist tools are increasingly facilitating the creation of perfect simulacra of a Commodore 64 or an SNES title. Birch even acknowledges that the genre and mood of Deadeus were shaped by the limitations of GB Studio, the engine he experimented with while developing it.

While arguments based on generational nostalgia apply equally to most retro-styled games, the growing availability of intuitive middleware points to an aspect of the phenomenon that is more horror-specific. Ted Hentschke, the mind behind the Dread X Collection project, believes that, as with the flood of found-footage movies that followed Paranormal Activity’s wide release in 2009, “the current popularity of retro-styled horror games has less to do with nostalgia than it does with the idea that any one of us can do it. When you look at Airdorf’s FAITH, that little pixel guy walking around, it doesn’t seem impossible that I could do that.

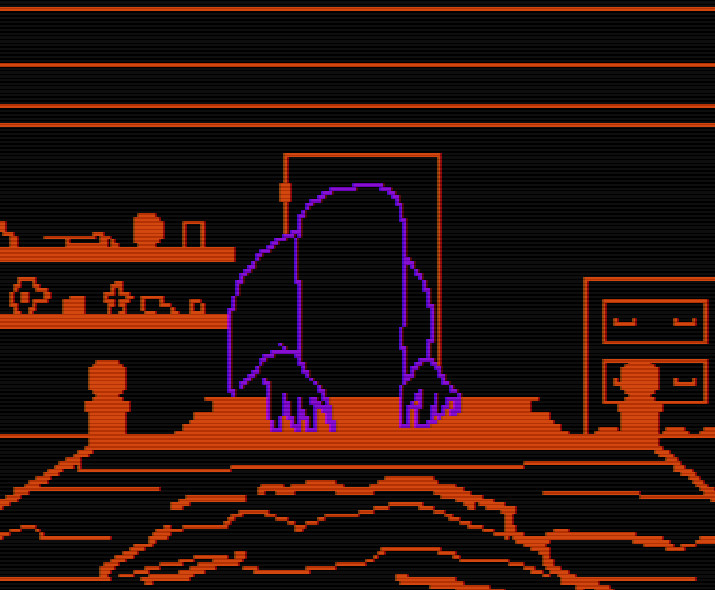

They can prime the player’s mind to be surprised and creeped out.

There’s a reason for that. Faith may be one of the most famous titles in the scene, an exorcism simulator that put to rest any silly notions that pixel art can’t scare the wits out of you, but it looks as if it could run on a 1982 Atari console. Mason Smith, better known as Airdorf, has an explanation for the capacity for such unorthodox visuals to unsettle that circles back to the blockbuster-fatigue argument. “Since retro-styled graphics have this innocent lo-fi quality to them, I think they can prime the player’s mind to be surprised and creeped out when the game goes after the player themselves, more so than your advanced 3D graphics.” While the homogeneity of marquee franchises will put off a segment of the audience in any genre, it is horror that, by its very nature, thrives on the unexpected.

This framing also serves to illuminate a deeper link between new retro horror and the cursed-media fad manifesting in the form of Ringu-inspired movies, explicitly meta games (such as Ivan Zanotti’s Imscared), and umpteen creepypasta threads. As Faith oscillates between pixel-art gameplay and jarringly incongruous rotoscoped cutscenes, the latter are so much more obviously advanced that they generate an impression of the game clambering up the ontological ladder and coming alive. Airdorf concedes that “although it was never meant to be a ‘cursed’ meta-game, I still admired the long-lasting effects those had on players. There are a few details that came from the ‘cursed’ game phenomenon, like the chromatic aberration effect that glitches the screen a little bit when something spooky happens.” Paradoxically, the flexibility of retro visuals allows for a broader arsenal of scares than the mandates of realism dictating the direction of big-budget horror.

At the same time, the question arises whether, with an expanding fan base and the arrival of the PS1 as an in-vogue reference point, the scene is inching toward an impasse. The long-running appeal of pixel art has already led to it being assimilated into the mainstream and, to some degree, stripped of its power to surprise. Could that be the future for other strains of new retro horror? More fundamentally, while people will always feel a personal sense of nostalgia for the console they grew up with, the PS1 was arguably the last piece of hardware to effect deep cultural change while introducing an instantly recognizable iconography. It is not that it’s too early to adopt, say, an Xbox 360 aesthetic; it’s that the very notion of it seems inconceivable. It is not unreasonable to suspect that we are running out of distinct visual styles to reclaim from the medium’s history, but whether that spells doom for the movement as a creative endeavor remains to be seen.

Wragg offers a thoughtful rebuttal. “Like impressionism in painting, the PS1 style portrays reality through the subjective vision of an artist. With smaller budgets and less at stake, these artists are free to create worlds that are surreal, strange, or uniquely beautiful in a way that you might not see in the mainstream industry. The intentional jankiness of the scene is like when punk music incorporates noise and reverb, a postmodern acceptance of the seams and imperfections within art that becomes part of the artwork itself.

In this light, it’s not the fondness for a particular era’s visuals that defines this haphazard movement whose instruments of revolution consist of blocky pixels, garish colors, and a whole lot of visual static. Instead, it’s the impetus to seek a language of creative expression outside accepted conventions. New retro horror is just the latest iteration of that never-ending quest.